Pumpkin Joe’s patch: where gardening and engineering work in perfect harmony

ISO-NE engineer puts degree to use growing giant pumpkins

ISO-NE engineer puts degree to use growing giant pumpkins

As the trees began to bloom last April, ISO New England System Planning associate engineer Joe Roberts prepared his Palmer, Massachusetts garden for planting season. Looking at the calendar, he noted the date of the Spencer (MA) Fair—August 30—and counted backwards four months. “April 30—that’s the day I need to get it outside,” he said. “I need those extra two months to get a big enough plant.”

On the morning of April 6, Roberts planted several seeds indoors in anticipation of the warmer temperatures that would come three weeks later. The shelter of his home kept the plants safe from the inevitable freeze-thaw cycles of the New England spring. Over the span of that month, Roberts narrowed his collection down to two plants and planted them in his garden on the cool morning of April 30.

“I like to garden, and I grow squash, tomatoes, beans, all kinds of stuff regularly,” Roberts said. “But I grow pumpkins competitively.”

ISO-NE Associate Engineer Joe Roberts with his 354-pound pumpkin.

ISO-NE Associate Engineer Joe Roberts with his 354-pound pumpkin.

Though unconventional, growing giant pumpkins is more common than you’d think. During September, state fairs across the country host competitions with monetary rewards for the largest pumpkin. Locally, the Eastern States Exposition (the Big E) in West Springfield hosts one of the most famous giant pumpkin-growing competitions in the country. Roberts recalled the day at the Big E early in his childhood that spiked his interest in the hobby.

“I’d often hear stories about my great-grandfather and how his ears of corn were so big that he only gave six to a dozen, or that his pumpkins were so big that he wouldn’t pick them, he’d just carve them out and kids would use them as playhouses,” he said with a grin. “Going to the Big E and seeing that pumpkins really could grow that large, that’s when I really got into it. The absurdity of it makes your jaw drop, it just looked like a fun thing to do. I knew I had to do it.”

Since those early childhood days at the Big E, Roberts has regularly taken shots at successfully growing a giant pumpkin. But he could never seem to grow his pumpkins large enough to compete, and then a hectic college schedule forced him to take a few years off. Now, with more time to focus on growing, he’s picking up right where he left off. The first step: find the root cause of his underwhelming pumpkins.

The fluctuating high- and low-temperatures in early spring can be damaging or even deadly to plants. To minimize risk, Roberts said he had no choice but to keep planting season weeks shorter than it should have been. Now a graduate of the electrical engineering program at UMass Amherst, he knew he found the solution.

“Early spring can be a wild card, you can get frost really any time during the month,” he said. “I had to figure out a way to lengthen my growing season. It led me to asking myself: why not just keep the soil warm? I mean, I have this fancy engineering degree, I might as well put it to good use.”

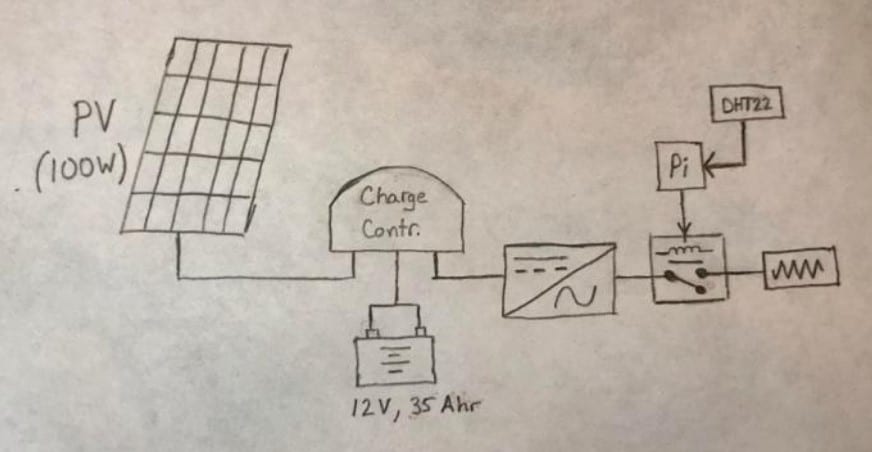

Using his electrical expertise, Roberts constructed a PV solar-powered system to recharge a battery that sends radiant heat into his pumpkin patch via resistance cables. He even presented his project to the Springfield, Massachusetts IEEE meeting last fall.

A sketch of Joe Roberts’ solar-powered soil warming system.

A sketch of Joe Roberts’ solar-powered soil warming system.

“I spec’d out what I needed—how much electricity for the soil warmer—and reversed it to determine the capacities for the batteries,” he explained. “If I need x capacity every day, how big does my solar panel need to be? I estimated what the solar panel output would be on average, and that kind of gave me enough information to build the system. It isn’t perfect, but it helps me get the pumpkin outside two weeks earlier.”

The two weeks have made a difference, too; Roberts has seen a steady increase in the size of his pumpkins every year. There isn’t a doubt in his mind that the soil warmer has helped, but Roberts explained that there is a whole lot more to his pumpkin-growing operation, especially his strict maintenance schedule.

“Watering is done in the morning and at night to keep the moisture steady,” he said. “If you let them dry out and then flood the plant with water, it can actually experience a rapid growth spurt and tear apart—they’ll literally blow up because they are growing too fast.”

The plants are also given organic spray treatments weekly. “I spray the plants for insects to keep the bugs down because they can end the season,” he said. “There’s a fungicide that helps to reduce some diseases and a seaweed concentrate that is just good for the overall health of the plant.”

But what separates Roberts’ pumpkins from the ones at the local farm? How do these pumpkins get so big? According to Roberts, the controlled, strategic use of minerals in the soil facilitate the rapid growth of the pumpkin.

“I use ‘the big three’—nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium,” he said. “Nitrogen is what gives the plants their green, phosphorus is for root and blossom development, and potassium helps with the hardiness of the plant. Depending on the time of year and the growth of the plant, I use a different mix of fertilizer to give the pumpkins what they need.”

After a productive summer, the hard work did eventually pay off. Weighing in at 354 pounds, Roberts’ 2019 pumpkin one-upped last years’ by 39 pounds, good enough to earn him fourth-place in the pumpkin growing contest at the Spencer Fair, where the stakes are a little smaller than the Big E.

“The pumpkins at the Big E, you’re talking about pumpkins over 1000 pounds to even be in the race there,” he said. “Maybe it’s a next year thing, but this year, I’m just happy that I beat my personal best.”

Next year, the goal is set for 500 pounds. Ask him how he’s going to do it, and Roberts will give you a simple answer.

“Good seed, good soil, and good luck.”

- Categories

- Features & Interviews